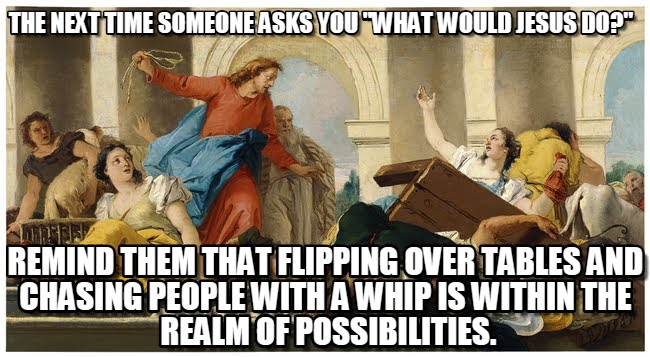

You may have seen the popular internet meme that says, “If anyone ever asks you ‘What would Jesus Do?’ remind them that flipping over tables and chasing people with a whip is within the realm of possibilities.”

That meme arises out of the Scripture passage John 2:13-22, where in verse 15, Jesus makes a whip and drives the livestock out of the temple. And while that meme is kind of humorous and not fully inaccurate, if we are being honest, it’s probably more likely that we enjoy it as a way to justify our bad behavior; it’s less about Jesus than it is about us.

When we get mad, we want to fight back. But at nearly every turn, Jesus calls us to peace and love. So what are we to make of this passage? Especially the part about the whip. At first glance and by popular accounts, this appears to be a weaponized Jesus. What are we supposed to do we do with that?

When I think about a whip, the first thing that comes to mind–aside from that catchy Devo song–is the sound that a whip makes. The crack of the whip. I can’t help but think of the movie Indiana Jones every time I hear one. In a movie where most of the villains carry guns, Indiana Jones seems to use that whip more than any other tool.

He uses it as a weapon against dangerous animals and adversaries, but he also uses it to pull levers from a distance, climb up steep cliffs, or swing across ravines just in the nick of time to get out of harm’s way.

And if we look back into the origin story of Indiana Jones, he first used a whip when he was aboard a circus train fleeing a gang. In that story, he accidentally falls into a wagon transporting a lion. Finding himself in a dire situation, he conveniently finds a lion-tamer’s whip nearby, which he uses to fend off the lion. But because he isn’t familiar with the whip, he accidentally snaps it back at himself. It strikes him under his lip, leaving a scar on his chin.

I can relate to that story because, on a mission trip to Mexico, a student in our group found a bull whip about 10-12 feet long at one of the markets. Of course, he purchased it without telling any of the leaders. It was only once we got back in the States that he showed us he had bought this thing. He was met with a lot of eye-rolls from our leaders, but not really knowing anything about whips, we just told him not to use it until he was home and his parents knew he had it.

Of course, this was in a county in Ohio where kids would skip school on the first day of hunting season and would go deer hunting with their parents as early as eight years old. It’s just a culturally different place than a lot of areas in the United States.

Anyhow, after several months, the student showed up with the whip at our house as a prop for Halloween. After we went trick-or-treating with the kids, it got left behind and ended up in a bin of Halloween costumes. Sometime after that, I found it, and in all of my infinite wisdom, I decided to see if I could knock over a can with it, “Indiana Jones Style.”

I don’t know if you’ve ever held a bull whip before, but they are heavier than you might guess. This one was brown, made of strips of leather wrapped around one other, forming a solid 8-inch handle at one end and winding out at the other end, where it was tied to create the tassels that would actually strike your object.

When we get mad, we want to fight back. But at nearly every turn, Jesus calls us to peace and love.

So I figured, how hard could this be, right? I mean, this kid had surely tried it out, and he was still in one piece. So, I line up the can a good distance from me, snap back that whip, and just like Indiana Jones, I crack myself right in the face. And boy did that thing hurt. It didn’t leave a scar, but it did bleed. Of course, that really ticked me off, which made me even more determined. So I practiced a bit until I could finally hit the can.

The point is that using a bull whip isn’t necessarily as intuitive as it might appear. Even later on in the Indiana Jones story, Indy has to practice to get good with one.

So I think we need to be careful not to confuse this with what Jesus was actually using. What he was using was probably less like an Indiana Jones bull whip and more like a 2-4 foot long bundle of cords. These aren’t really even comparative instruments. And I think that it’s easy enough for us to get them confused, because there is no good reason that most of us would know any better.

I’ve actually read some scholars try to make the argument that Jesus painstakingly took the time to craft an actual whip in the middle of the market. But when we look at the larger narrative of who Jesus is, this doesn’t seem to fit. The passage at hand actually seems to be more of a real-time incident; he goes into the Temple, sees what is happening, grabs some small “cords,” which were usually “rushes or “reeds” used to make ropes, and just starts chasing the animals out of the temple.

Note: Jesus is driving away both the sheep and the cattle, but not people. Memes and pastors alike often make it sound like Jesus is just randomly beating money changers and random passers-by in this scene, but that isn’t what is happening. This is more like if you saw someone tagging the side of your parents’ car. You’d quickly grab whatever you could to chase them off. This, I think, is more the ethos behind what Jesus is doing. It’s like he’s saying, stop messing with what’s not yours! Show some respect!

In fairness, it’s more than that too. Jesus is definitely also making a scene. He’s pouring out coins and flipping tables. That too can sound more aggressive than it actually was, but as far as we know, he doesn’t harm anyone. He is definitely being disruptive, but no one is hurt in this incident.

So what is this about? Fundamentally, it’s a justice issue. The money changers would actively defraud people of their money at the Temple as people came to make sacrifices to get right with God. People would need a sacrifice to atone for their sin, so they would bring an animal to the Temple. But once there, they would often be told that their sacrifice wasn’t good enough and that they’d have to buy a “better” animal. But the better animal wasn’t actually any better; it was all just a scam for the money changers to make money on the margins of the transactions. The victimized people would do it because they didn’t want to risk being out of favor with God.

Jesus knows this, because almost everyone knew it in his day. It’s likely that his own family had been victims of this injustice, too. It’s a systemic issue, where people were being taken advantage of by the primary religious institution of the time. Jesus wants to be clear that this is not what God stands for.

We see this kind of behavior all the time in modern scenarios: televangelists that scam people out of their money by inciting fear, megachurch pastors who use their congregation’s tithes to buy a personal jet, fundamentalist churches that try to make their congregants feel better by pointing out how bad some other group of people are… Corruption happens all around us, in business, in government, and even in our religious institutions.

We see these injustices. Some of us live through their systemic effects on a daily basis.

But we shouldn’t confuse our wicked desire for some kind of personal retribution with what Jesus is doing in this passage. Jesus is not bringing reputation in this story, but rather, he is giving a warning. A warning that when we hurt others, we hurt ourselves as well. The fact is that when we bring out a whip in our context, it’s likely that it’s going to hurt us first, and maybe most.

In the midst of an unjust system that had been normalized, Jesus is trying to get folks’ attention to remind them that “Humanity is better than this! Stop acting like we aren’t.” And that is because Jesus knows that we are creatures made in the image of God. Jesus sees in the people around him–and in you and me–the potential of what we can be, but at some point, that means that we simply have to stop allowing injustice to continue.

And that is because Jesus knows that we are creatures made in the image of God. Jesus sees in the people around him–and in you and me–the potential of what we can be, but at some point, that means that we simply have to stop allowing injustice to continue.

This may upset some folks. It may rock the boat. But to let it continue is to participate in evil, when God calls us to participate in redemption and caretaking instead.

What is most fascinating about this passage to me, though, is where this narrative happens in the Gospel. In John’s account, this story happens right after Jesus’ first miracle early in his ministry. But in the other three Gospels–Matthew, Mark, and Luke–the story happens towards the end of his ministry, and all three of those accounts say nothing about a whip.

Why would that be? It may be that Jesus went through this Temple-cleansing exercise, seeking to bring about justice, more than once in his ministry. It could be that he went to the Temple in the account we read in John, and once he left, everyone just went back to business as usual.

Systemic injustices are not easy to undo. So maybe Jesus comes back again later to remind people once more.

What is interesting is that after he does this in Matthew 21:12-17, it seems like the average person understands that this is a warning in love–and that Jesus is standing for God. I say that because in verse 14, we read that his actions result in the blind and the lame coming into the Temple. He heals them, and children proclaim Hosannas because of the wonderful things he’s done.

Mark and Luke’s Gospels both articulate that after the chief scribes and the priest heard what Jesus said, and presumably saw what good he did, they kept looking for a way to kill him. Jesus is literally healing people, and the powers-that-be want him dead. Why? Because they want to be in charge.

Think about that a minute. When we want vengeance–when we want revenge–why do we want it? Usually, because we want to be in charge. We want to crack the whip.

Yet, deep down we know that God is in ultimately in charge, not us. So maybe instead of coveting an authority that isn’t ours, we’d be better off following Jesus’ lead, speaking up for God in the midst of an unjust establishment until the people around us start to see who really represents God.

Because it’s never by retaliation that we advance. It’s only in love that we win.

Reality Changing Observations:

1. Why do you think Christians try to project vengeance and aggression on Jesus? What are we trying to justify?

2. What might it cost us to stand up for what is right and for who God is?

3. Where can we confess a spirit of anger and vengeance in our own lives? In our church? In our community and nation? What is the way forward?